Joseph-Édouard Cauchon, Date of Birth, Place of Birth, Date of Death

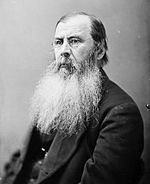

TweetJoseph-Édouard Cauchon

Canadian politicianAbout Joseph-Édouard Cauchon

- Joseph-Édouard Cauchon, (December 31, 1816 – February 23, 1885) was a prominent Quebec politician in the middle years of the nineteenth-century.

- Although he held a variety of portfolios at the federal, provincial and municipal levels, he never achieved his goal of becoming the Premier of Quebec. Born to a well-established family of seigneurs, Cauchon received a classical education at the Petit Séminaire of Quebec from 1830 to 1839, and subsequently studied law.

- He was called to the Quebec bar in 1843, but never practised.

- Instead he turned to journalism, working for Le Canadien from 1841 to 1842, and launching his own Le Journal de Québec in December of the latter year.

- This paper was known for its sharp political wit and generally supported Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine's French Canadian Reformers during its early years. In 1841, he published an elementary treatise of physics entitled Notions élémentaires de physique, avec planches à l'usage des maisons d'éducation. Cauchon himself entered political life in 1844, winning election for the riding of Montmorency in the Province of Canada's legislature.

- He defeated a Mr.

- Taschereau by 475 votes to 147, and sat with Lafontaine's French Canadian group on the opposition benches for the next three years. Lafontaine's party won a major victory in 1847, and Cauchon was re-elected by acclamation.

- He did not, however, join the cabinet of Lafontaine and Robert Baldwin. Cauchon supported the union of Canada East and Canada West as a guarantor of rights for both regions and sought to have the bilingual Augustin-Norbert Morin elected as speaker of the provincial legislature.

- When Francis Hincks replaced Lafontaine as Premier in 1851, Cauchon's position was one of ambivalence.

- He opposed Hincks's alliance with the Clear Grit faction (which he described as "socialist and anticatholic"), and turned down Hincks's offer to become assistant Provincial Secretary.

- While he did not abandon the Reform cause entirely, his newspapers's criticisms of the Hincks government weakened the ministry's position in Quebec. Cauchon was himself re-elected in 1851 and 1854, defeating one Mr.

- Glackemeyer by 883 votes to 529 on the latter occasion.

- His political position in 1854 was ambiguous, and he held some hopes of replacing Hincks as a coalitionist Premier when the overall results proved inconclusive.

- He abandoned this plan, however, to support the alliance of Allan Napier McNab's Conservatives with the French Canadian bloc (then led by Morin) and a part of Hincks's Reform group.

- In the year that followed, Cauchon supported the government's decisions to eliminate the seigneural system (over Louis-Joseph Papineau's objections) and secularize the clergy reserves.

- In 1855, he introduced a bill to make the Legislative Council elective; this was passed into law, and came into effect the following year. Later in 1855, Cauchon was appointed to the McNab–Étienne-Paschal Taché cabinet as Commissioner of Crown Lands.

- He resigned in April 1857, when his government refused to allocate funds for a railway on the north shore of the Saint Lawrence River.

- Cauchon remained a member of the Parti bleu, however, and was re-elected in the general election of 1857. Cauchon voted against his party on some occasions in 1858, and spoke out against its early support of Canadian Confederation.

- Nevertheless, he was appointed in 1861 as Minister of Public Works in the George-Étienne Cartier-Macdonald cabinet, and held this position until the Cartier-Macdonald government was defeated in the house the following year.

- Cauchon was returned by acclamation in the general election of 1861, and defeated a Mr.

- Tourangeau by 526 votes to 367 in 1863. When the Conservatives returned to power in March 1864, Cauchon was again chosen as Public Works minister.

- He was forced to resign this position after the creation of a "Grand Coalition" ministry in August, though he continued to support the government from the back benches.

- Despite his previous opposition, he also emerged as a leading supporter of the confederation plan.

- In 1865, he published (in French and English) a work entitled The union of the provinces of British North America, which rejected his earlier opposition to the plan. While retaining his seat in parliament, Cauchon also served as mayor of Quebec City from 1865 to 1867.

- It is difficult to determine what he accomplished, as he never published a report during this period. After Confederation was achieved in July 1867, Cauchon was called upon to become the first Premier of Quebec.

- He was unable to accomplish this task, however, as his plans to include an anglophone in cabinet broke down on the issue of educational funding for the province's Protestant minority.

- Cauchon opposed the creation of a Protestant Superintendency for the province, while all of his potential anglophone ministers supported it.

- Accordingly, Cauchon stood aside, and Pierre Chauveau became the province's first Premier instead.

- Despite this setback, Cauchon was re-elected for Montmorency to both the federal and provincial parliaments later in the year. Rejected in his bid to become Quebec Premier, Cauchon still sought higher office.

- In October 1867, he demanded that the Conservative government appoint him to the Senate of Canada, and allow him to be chosen as its first speaker.

- Narcisse-Fortunat Belleau was accordingly convinced to resign his Senate seat, and Cauchon took his place on November 2, 1867, becoming speaker three days later.

- His appointment was extremely unpopular with senators from both parties, and Cauchon subsequently identified himself as an Independent Conservative.

- The affair may have contributed to Cauchon's defeat at the hands of John Lemesurier in a bid for re-election as Quebec City's Mayor one month later.

- Despite the unpopularity of his appointment, Cauchon remained Speaker of the Senate until June 30, 1872 (though he stepped down on a temporary basis on two occasions, for eleven days in total).

- While in Ottawa he lived in Stadacona Hall in Sandy Hill. Cauchon was re-elected by acclamation to the Quebec assembly in 1871 and resigned his Senate seat in 1872 to run for the House of Commons again.

- This time running in Quebec Centre, he was opposed by an Anglophone Protestant named James Gibb Ross.

- The resulting election was divided on sectarian lines, and was extremely violent.

- Cauchon won by 964 votes to 694; he returned to parliament as an Independent Conservative and was not specifically aligned with either party. In 1873, Cauchon wanted to replace N.

- F.

- Belleau as lieutenant governor of Quebec, but was rejected by the Macdonald government due to his large number of enemies.

- He also wanted to become Quebec leader of the federal Conservative party after Cartier's death, but was too unpopular within the party.

- Following these rejections, he began to align himself with the opposition Liberals, joining the party when the Pacific Scandal brought down Macdonald's government later in the year.

- Cauchon resigned his seat in the Quebec legislature in February 1874 when his "dual mandate" became illegal, and thereafter focused his attentions on federal advancement. Cauchon's presence in the Liberal Party was a matter of convenience for both sides.

- Cauchon provided the Liberals with a link to various Catholic concerns in Quebec, and helped the party rebuild a provincial network.

- In return, Cauchon was appointed to cabinet as President of the Privy Council on December 7, 1875.

- Liberal Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie subsequently wanted to promote him to Minister of Justice, but was unable to do so because of divisions in the party.

- Cauchon was, however, promoted to Minister of Inland Revenue on June 8, 1877. As before, Cauchon was a leading source of division in his party.

- Wilfrid Laurier emerged as a leading opponent of Cauchon among the Quebec Liberals, and was successful in having him removed from cabinet in October 1877.

- As compensation, Cauchon was appointed the third Lieutenant Governor of Manitoba, replacing the retiring Alexander Morris. Cauchon's appointment was met with apprehension among Manitoba's anglophone residents.

- The province's population was divided on ethnic, linguistic and religious lines at the time, and there was often strong antagonism between members of different communities.

- Many within Manitoba's majority anglophone population believed that Cauchon would refuse to uphold their legal rights.

- This supposition proved false, but Cauchon still reserved approval of an 1878 bill that eliminated the printing of government legislation in French. While the previous lieutenant governors of Manitoba had been interventionist figures, Cauchon was generally content to assume a more ceremonial role.

- This was a reflection of the province's political maturity and its ability to govern without direction from its formal executive. Cauchon's term ended on December 1, 1882, although he remained in Manitoba after this time.

- Already wealthy from his business activities in Quebec, he had made a further fortune on railway speculation in the western province (estimates of his earnings range from half a million to a million dollars).

- He was caught in a market downturn just as his term in office came an end, however, and was forced to sell his luxurious Winnipeg mansion in 1884.

- He then moved to the Qu'Appelle Valley (in modern Saskatchewan), and lived in somewhat reduced circumstances until his death the following year.

Read more at Wikipedia

See Also

- Famous People's Birthdays on 31 December, Canada

- Famous People's Birthdays in December, Canada

- Famous lawyer's Birthdays on 31 December, Canada

- Famous lawyer's Birthdays in December, Canada

- Famous politician's Birthdays on 31 December, Canada

- Famous politician's Birthdays in December, Canada

- Famous journalist's Birthdays on 31 December, Canada

- Famous journalist's Birthdays in December, Canada

Date of Birth:

Date of Birth:  Place of Birth: Quebec City, Quebec, Canada

Place of Birth: Quebec City, Quebec, Canada